In mid-March 2020, just as the pandemic struck NYC, The Laundromat Project signed a 10-year lease on its first ever long-term home, in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. The building, a two-level storefront at 1476 Fulton Street, will become a creative hub—a space for community and neighborhood gatherings; art and community-building workshops; and collaborative programs with Bed-Stuy neighbors, arts & culture entities, and civic initiatives. It will also house The LP’s administrative HQ—the space where our staff will eventually work full time.

To manifest this multi-purpose, welcoming, POC-centered art-and-community space, The LP brought on architect Nandini Bagchee, whose architecture practice and research interests include the aesthetics of Black and brown spaces, and the ways social justice and built environments connect.

Media and Storytelling staff Emma Colón and Julia Mata spoke with Nandini and LP Executive Director Kemi Ilesanmi about the design of the space and POC institution building.

This interview has been edited for brevity.

Emma Colón (EC): Kemi and Nandini, you’ve known each other since before the 1476 Fulton project. How did you initially meet?

Kemi Ilesanmi (KI): I have a feeling that Nandini remembers a little more clearly than me, but we met at the Walker Art Center in 2002.

Nandini Bagchee (NB): I moved to Minneapolis briefly to work on the Walker—a few of us were there for two years working on the design of the extension to the museum for the Basel-based architectural practice Herzog & de Meuron. I remember Kemi, a curator at the time, giving us architects a tour of the sculpture garden. Over time, through our mutual friend Claire Tancons (also a Walker curator) we became closer. What are the odds of finding two brilliant black women curating at an art institution in Minneapolis at that time! We did things together, I had a car and I remember driving them both around and going to various events and mingling at the Walker. So now I’ve gone from chauffeur to architect!

Julia Mata (JM): So Kemi, curious to know, what made you think that Nandini would be a good fit for the 1476 Fulton project, and what were your ambitions for this new home for The Laundromat Project when you asked Nandini?

KI: After my time at the Walker, I ended up in New York working at Creative Capital Foundation, and Nandini was down the street working with a group of activists at a famous building in NoHo [the Peace Pentagon, at 339 Lafayette Street, which housed numerous social justice and activist orgs and closed in 2016]. At some point while we were working half a block away from each other, she reached out and asked if we could meet up and chat about her work: she was trying to save the building which was basically under gentrification pressure, and many really incredible social justice organizations and collectives were about to be homeless. So that conversation connected us. Eventually I came to work at The LP. Nandini brought her students from City College to visit Kelly Street two or three years ago, and also joined us for a Field Day festival in Harlem once.

So we had this history. Over dinner in the spring, a week before we saw the space that is now 1476 Fulton, Nandini had expressed interest in the project. As the staff and board toured the space, we asked Nandini if she wanted to come give us feedback and see if it seemed like an exciting space to play with. And that was that!

JM: Nandini, what did you know about The LP already when Kemi told you about this project, and how did that inform your initial thoughts or visions?

NB: Yeah, so Kemi spoke a little bit about my interest in social justice organizations and the way spaces impact people’s organizing work. I have researched how important access to space is for grassroots organizing, and wrote a book called Counter Institution: Activist Estates of the Lower East Side about offices, storefronts, and other collective spaces where activists have organized against war, for housing, but also set up creative communities that experiment with and build culture. A space that inspired me tremendously was a Puerto Rican community center called CHARAS, run out of a repurposed schoolhouse for over 20 years in Loisaida. So I am really involved in this concept from a historical standpoint of how people use space to leverage different kinds of social justice projects, where art, culture, housing, everything comes together in these makeshift interiors that people appropriate and make their own. Right now, real estate is so prohibitive and expensive, there’s little room left for this type of creative production of space. So when Kemi mentioned that [The LP] in fact had gathered up the resources and was searching for a storefront—I was really very excited. I definitely wanted to be involved.

The interesting thing about The LP was that historically there wasn’t any permanent space dedicated to them—they’d just sort of co-opt the laundromat or other spaces. The Laundromat Project would happen wherever people are, as opposed to within a specific gallery or museum, and I really loved that idea.

NB: So then when they were actually looking for space that would bring people together for work, play, creativity, making, all into one space—it sounded like all the things I’d written about in the book were here in this project. While I love the spontaneity of the LP mission, having access to a particular physical space, a headquarters, will give visibility to their work and ground them in the Bed-Stuy neighborhood over time.

KI: Knowing Nandini and having conversations over the course of 20 years, we built up a sense of trust. Having a woman of color, an immigrant, as the architect and co-creator of the space was also important—being able to bring in some of the life and professional experiences that mirror the folks we work with was something that I was interested in.

JM: Nandini, in thinking about the topic of your book, and people appropriating spaces and transforming them to fill whatever purpose they need, I’m thinking about what this opportunity [with The LP] means: to be able to construct a space for community gathering that already has all those things you would want—to be able to fully conceptualize it from the ground up. In your last in-person meeting with LP staff, you talked about POC aesthetics as a driving factor for how you envisioned the space. Can you say a little bit more about that? What does that mean to you, and how did you envision that manifesting in this new building?

NB: The way we started was I actually visited the old LP office in Harlem, and we all sat around a table and discussed what the needs were. There’s a lot of things happening all at once: there’s work space, then community space for doing projects; there’s going to be events in the evenings, and also a space for the display of artwork and materials—so it’s very multipurpose. On the one hand, there’s a desire for it to be a special place to foster creative community; on the other, [the staff] didn’t want it to be over-designed, and they wanted it to fit in on the block. So everyone at The LP put together Pinterest boards with design ideas and elements they thought were important to include, and this became my reference document—things like a chalkboard to write the week’s schedule, coat hooks, art drying racks, quiet rooms, accessible storage, tiles, color, pattern, natural materials, and so on.

NB: I think what we’ve tried to design is something that’s somewhere in between having its own identity, saying, “Yes, this is The Laundromat Project space,” while also facilitating the concept of participation in the art-making process. The kind of projects that The LP supports, they’re not in a bracket of any sort. So I think of the design of the space as also being fluid. It’s comfortable, it’s colorful, but there is room to expand into. It’s not precious, and it’s not prescriptive or making people feel like they can’t come in. It has to be kind of fearless, and at the same time open ended.

We have a color scheme that Kemi and I were discussing this morning, which comes from The LP’s graphic design color palette. There’s going to be a lot of natural wood and brick, and just to offset that warmth, we’re picking a bright but cool color palette to accentuate the built storage and seating. Purple is a color everyone loved. Added to the trademark watery LP blue—an unusual combination—it creates a striking effect. Black and white tile patterns refer to the simplicity of the geometric Malian mudcloth fabric. Creating an atmosphere with paint, bringing more light into the space—making more with less.

NB: So those are the kinds of ways in which we’re designing it from a colors and material standpoint, but there has also been a lot of conversation around access. We’ve been addressing accessibility, both from how a wheelchair would enter, for example—that’s one kind of access—to what makes people feel like they can be around, and not feel like someone’s watching them, like when you walk into a museum. We’ve tried to create hangout nooks and crannies, and there’s a magazine section, so that people can feel free to just be there and not necessarily do anything, right? As well as come in and participate in the events and organized programming.

KI: Back to your “not-precious” comment, Nandini—if I can just add to what you were saying about wanting to both be fearless and not precious, both welcoming and special. People can read design. We’re really trained at this point to go, “Oh, that’s not for me. I don’t know what that is, but I’m not the person that they want there.” So part of the conversation from the beginning has been to not have that feeling towards our neighbors in Bed-Stuy, especially those who are Black, POC, low income, or disabled.

How can we communicate that “you are welcome here” as opposed to “you are not welcome here?” Design is a language, and as humans in cities—in gentrifying cities—we are 100% capable of reading when a space is not for us.

EC: Is there anything else you could share about how you think an art space can be welcoming? Because there is a lot of discussion about how the architecture of art spaces is unwelcoming, specifically to POC communities. What other choices in the design and architecture are you making to communicate a POC aesthetic, or a welcoming aesthetic?

KI: Our timeline for moving into the space has been significantly slowed down due to the pandemic. As a result of that, Nandini has had the time to visit the space many times, to meet contractors and various things, and has been able to actually spend time on the block and in the environs—to go to the Bengali shop down the street, the Senegalese shop, the hair shop.

Nandini is Indian, I’m Nigerian and Black American, and many of us on staff and people in Bed-Stuy are coming from Black and/or POC immigrant communities. For me, regarding POC aesthetics, the number one thing I think of is our relationship to color, and our fearlessness around it. Many Black and brown cultures like a pattern, and we like color.

Being able to work that in is going to communicate, “This is a space for you.”

NB: There is color, there are the patterns, but it’s also about how things are put in place. I spoke earlier of the flexibility. This is an active community space where creativity is encouraged and things are made—it’s not just where you go to see things. There are workshop areas that can be transformed into lecture spaces as well as lunch rooms.

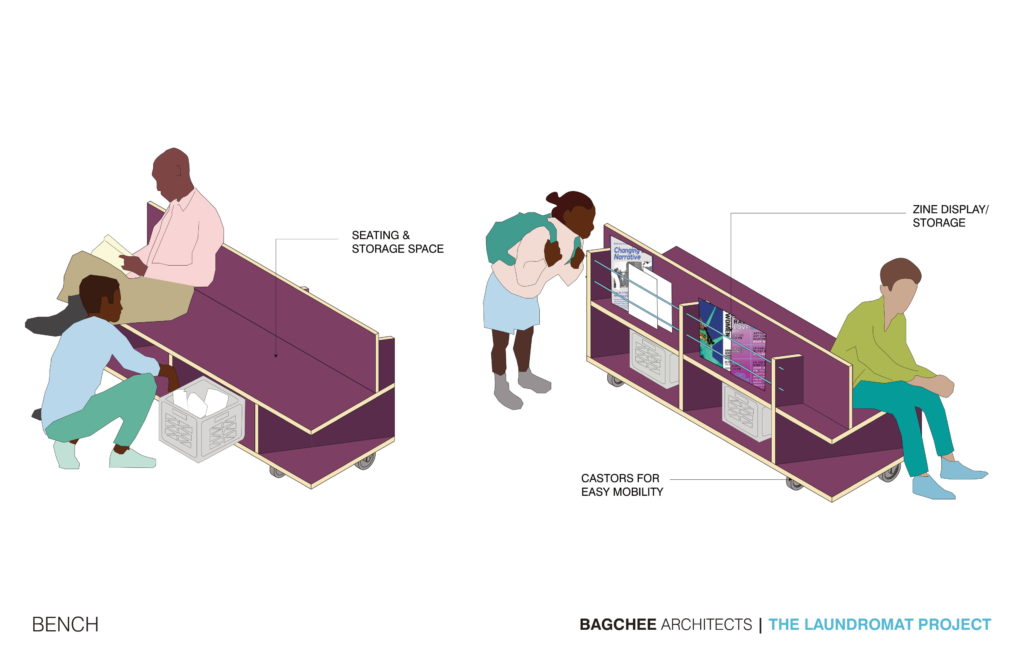

We’ve introduced elements that allow the occupants to change the space according to their programming needs. For example, the cushions that you can move around and sit on the floor for art making and events; the chairs that fold and hang on the brick walls; and the mobile benches with magazines and brochures on the back. The benches are on wheels and can go in and out of the storefront, or be on the sidewalk during events and information sessions.

These are multi-functional objects that can wander all the way from Restoration Plaza to the subway stop, and be anywhere in between—wherever you decide.

NB: We’ve also been tuning in to the way in which things are already happening on the street—subtle things, like how the regular stores on Fulton always have their name very big on the awning, with the street address of the place, and the phone number. And so in our design of the signage we’ll be focusing on things like that, to say that this is a New York storefront, while simultaneously announcing that this is not a commercial venture. Rather than design a retail storefront, we’ll leave the front window open for different kinds of art projects sponsored by The LP.

KI: And going back to the moving bench Nandini mentioned: the multi-use of that—being a piece of furniture, a bench, and also distributing magazines and art, I think that combination of something beautiful with something purposeful really connects to POC aesthetics—I think our extreme resourcefulness is a POC superpower.

JM: One last question. Knowing that we will be here long term, and that the community is going to shape how the space is used over time, I’m curious to know from both of you, what are your visions of the space 1 year from now, 5 years from now, 10 years from now?

KI: One year from now, I want it to be full of people. Right now that literally feels like a reach. Six months ago I might have answered that differently, but right now that’s what feels exciting to me—to actually have 20 or 30 people in this space at a time, and to have it feel safe and beautiful and wonderful and welcoming and all the things. That’s all I want. I’m pretty sure that we can do that, I feel like the universe is shining down on us.

In five years, I want it to be a space that feels lived-in, where there’ll be some scuffs and signs of life, and where people are doing and making, and feeling comfortable, and feeling a sense of ownership. Doing things that we couldn’t have predicted, because people will feel it’s their space.

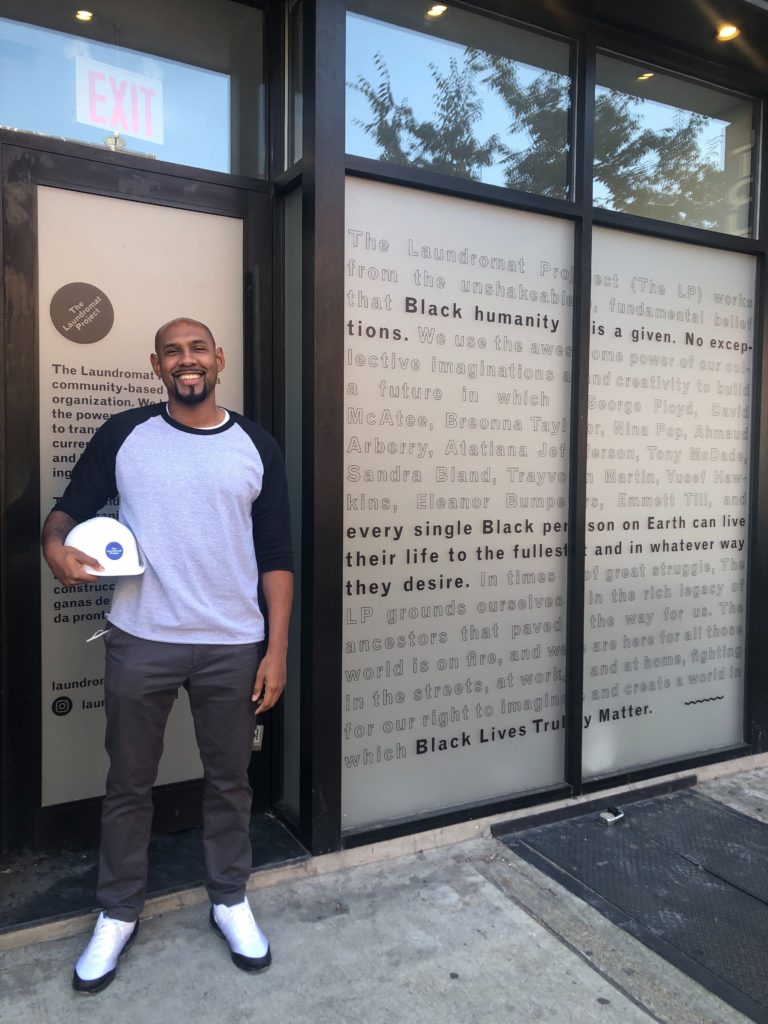

NB: This summer as we waited for work to resume and permits to be issued, I’ve been going by 1476 Fulton to see what’s going on. A couple of times I’ve seen passersby stop at the storefront where the Black Lives Matter statement is up, looking at it and pausing and saying, “Oh, what’s happening here? I wonder what’s coming.” They seem interested, excited, people, especially POC right now, want change that will be for them and about them. And so part of what one hopes will happen after 5 years, 10 years, is that The LP at 1476 Fulton will become a part of someone’s life.